This is the time of year when many parents, particularly those of children with second year Early Childhood students, are faced with deciding where their child will attend school for the coming year(s). Kindergarten can seem like a natural transition to a local public school or an elementary program you may have had your eye on for some time. However, the third year in an Early Childhood program is a very magical experience that we hate to see our students missing out on. Below is an article written by Tim Seldin and Dr. Elizabeth Coe, experienced Montessori teachers, parents, trainers and advocates, about the benefits of kindergarten in a Montessori environment.

Why Montessori for the Kindergarten year?

By Tim Seldin with Dr. Elizabeth Coe

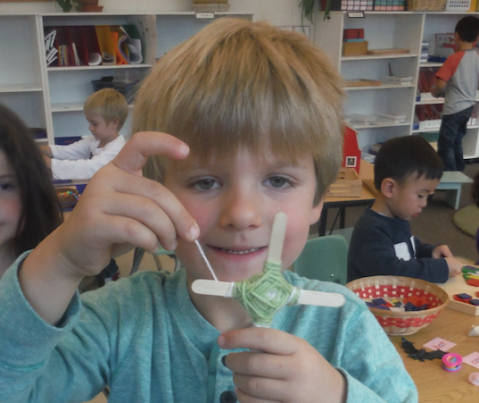

Magnolias Third Year student works on a botany project.

It’s re-enrollment time again, and in thousands of Montessori schools all over America parents of

four-almost-five-year-olds are trying to decide whether or not they should keep their sons and

daughters in Montessori for kindergarten or send them off to the local schools.

The advantages of using the local schools often seem obvious, while those of staying in

Montessori are often not at all clear. When you can use the local schools for free, why would

anyone want to invest thousands of dollars in another year’s tuition? It’s a fair question and it

deserves a careful answer. Obviously there is no one right answer for every child. Often the

decision depends on where each family places its priorities and how strongly parents sense that

one school or another more closely fits in with their hopes dreams for their children.

Naturally, to some degree the answer is also often connected to the question of family income as

well, although we are often amazed at how often families with very modest means who place a

high enough priority on their children’s education will scrape together the tuition needed to keep

them in Montessori.

When a child transfers from Montessori to a new kindergarten, she spends the first few months

adjusting to a new class, a new teacher, and a whole new system with different expectations.

This, along with the fact that most kindergartens have a much lower set of expectations for fiveyear-olds

than most Montessori programs, severely cuts into the learning that could occur during

this crucial year of their lives.

This Sequoias Third Year Student gets creative.

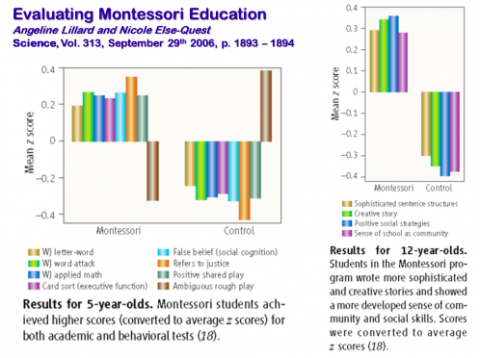

Montessori is an approach to working with children that is carefully based on what we’ve learned

about child development from several decades of research. Although sometimes misunderstood,

the Montessori approach has been acclaimed as the most developmentally appropriate model

currently available by some of America’s top experts on early childhood and elementary

education. As a “developmental” approach, Montessori is based on a realistic understanding of

children’s cognitive, neurological and emotional development.

One important difference between what Montessori offers the five-year-old and what is offered

by many of today’s kindergarten programs has to do with how it helps the young child to learn

how to learn. A great deal of research shows that quite often students in traditional programs

don’t really understand most of what they are being taught. Harvard Psychologist and author of

The Unschooled Mind, Howard Gardner, goes so far as to suggest that, “Many schools have

fallen into a pattern of giving kids exercises and drills that result in their getting answers on tests

that look like understanding.”

But several decades of research into how children learn have shown that most students, from as

young as those in kindergarten to students in some of the finest colleges in America do not, as

Gardener puts it, “understand what they’ve studied, in the most basic sense of the term. They lack

the capacity to take knowledge learned in one setting and apply it appropriately in a different

setting. Study after study has found that, by and large, even the best students in the best schools

can’t do that.” (On Teaching For Understanding: A Conversation with Howard Gardner, by Ron

Brandt, Educational Leadership Magazine, ASCD, 1994.)

Montessori is focused on teaching for understanding. In a primary classroom, three and fouryear-olds

receive the benefit of two years of sensorial preparation for academic skills by working

with the concrete Montessori learning materials. This concrete sensorial experience gradually

allows the child to form a mental picture of concepts like “how big is a thousand, how many

hundreds make up a thousand”, and what is really going on when we borrow or carry numbers in

mathematical operations.

The value of the sensorial experiences that the younger children have had in Montessori is often

under-estimated. Research is very clear that this is how the young child learns, by observing and

manipulating his environment. The Montessori materials give the child a concrete sensorial

impression of an abstract concept, such as long division, that is the potential foundation for a

lifetime understanding of the idea in abstraction. Because Montessori teachers are

developmentally trained, they normally know how to present information in an appropriate way.

Third Year Students from the Willows Class lay out the decimal system in preparation for adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing in to the thousands.

What often happens in schools is that teachers are not developmentally trained and children are

essentially filling in workbook pages with little understanding and do a great deal of rote

learning. Superficially, it may appear that they have learned a lot, but the reality is most often

that what they have learned was not meaningful to the child. A few months down the road, little

of what they “learned” will be retained and it will be rare for them to be able to use their

knowledge and skills in new situations. More and more educational researchers are beginning to

focus on whether students, whether young or adult, really understand or have simply memorized

correct answers.

In a few cases, kindergarten Montessori children may not look as if they are not as advanced as a

child in a very academically accelerated program, but what they do know they usually know very

well. Their understanding of the decimal system, place value, mathematical operations, and

similar information is usually very sound. With reinforcement as they grow older, it becomes

internalized and a permanent part of whom they are. When they leave Montessori before they

have had the time to internalize these early concrete experiences, their early learning often

evaporates because it is neither reinforced nor commonly understood.

In a class with such a wide age range of children, won’t my five-year-old spend the year taking

care of younger children instead of doing his or her own work? The five year olds in Montessori

classes often help the younger children with their work, actually teaching lessons or correcting

errors. Many Montessori educators believe that this concern felt by some parents is very

misguided.

Anyone who has ever had to teach a skill to someone else may recall that the very process of

explaining a new concept or helping someone practice a new skill leads the teacher to learn as

much, if not more, than the pupil. This is supported by research. When one child tutors another,

the tutor normally learns more from the experience than the person being tutored. Experiences

that facilitate development of independence and autonomy are often very limited in traditional

schools.

By the end of age five, Montessori students will often develop academic skills that may be

beyond those of advanced students. Academic progress is not our ultimate goal. Our real hope is

that they will feel good about themselves and enjoy learning. Mastering basic skills is a side

goal.

Montessori children are generally doing very well academically by the end of kindergarten,

although that is not our ultimate objective. The program offers them enriched lessons in math,

reading, and language, and if they are ready, they normally develop excellent skills. The key

concept is readiness. If a child is developmentally not ready to go on, he or she is neither left

behind nor made to feel like a failure. Our goal is not ensuring that children develop at a

predetermined rate, but to ensure that whatever they do, they do well and master. Most

Montessori children master a tremendous amount of information and skills, and even in the cases

where children may not have made as much progress as we would have wished, they usually

have done a good job with their work, wherever they have progressed at any given point, and

feel good about themselves as learners.

This Third Year Student from the Aspens class refines his small motor skills in the Practical Life area.

About the Authors

Dr. Elizabeth (Betsy) Coe is the Past President of the American Montessori Society and Director

of the Houston Montessori Teacher Education Center in Houston, Texas.

Tim Seldin is the President of the Montessori Foundation and Headmaster Emeritus of the Barrie

School in Silver Spring, Maryland.