Social Development in the Montessori Classroom

Through the years I have often been asked about Montessori students and their development of social skills. Some parents, when considering a Montessori education, become concerned that because of the size of the facility, the mixed age groupings, or the limited number of classrooms that their child will somehow be “missing out” on some aspects of social development. The short answer is that although there might not be as many children on our campus, the opportunities to develop socially are unlimited in the organization of the classrooms and curriculum.

“Social life does not consist of a group of individuals remaining close together, side by side, nor in their advancing en masse under the command of a captain like a regiment on the march, nor like an ordinary class of school children. The social life of man is founded upon work, harmoniously organised and upon social virtues – and these are the attitudes which develop to an exceptional degree amongst our children. Constancy in their work, patience when having to wait, the power of adapting themselves to the innumerable circumstances which present themselves in their daily contact with each other, reciprocal helpfulness and so on, are all exercises which represent a real and practical social life and which we see, for the first time, being organised amongst the children in a school. In fact, whereas schools used to be equipped only so as to accommodate children, seated passively side by side, who were expected to receive from the teacher (we might almost say in a parasitic manner), our schools, on the contrary, have an equipment which is adapted to all those forms of work which are necessary in an active and independent little community. The individual work in which the child is able to isolate himself and to concentrate, serves to perfect his individuality and the nearer man gets to perfection, the better is he able to associate harmoniously with others. A strong social movement cannot exist without prepared individuals, just as the members of an orchestra cannot play together harmoniously unless each individual has been thoroughly trained by repeated exercise when alone.”

Maria Montessori

The Early Childhood Aspens class invites the Willows class to a formal lunch to celebrate their friendship in November.

As her philosophy developed, many standards were set into place which help a student develop socially. Some of those include:

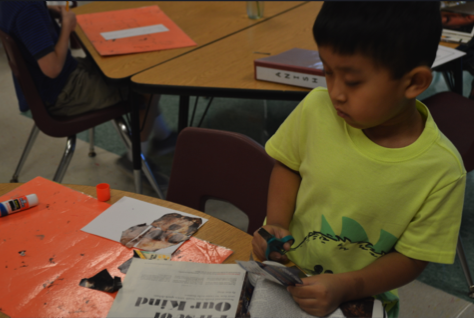

- Grace & Courtesy: An essential part of the Montessori curriculum is the opportunity for children to develop skills of grace and courtesy. Children learn to interact appropriately with one another through dialogue with adults, they learn to greet and host guests into their classroom, and they learn to dialogue with their peers in classroom meetings. As early as three years old students use the “peace table” as a place to they learn to recognize personal feelings and express themselves. They often share a “peace object” of some kind (ie; rock, flower…) that can be passed back and forth as they work to solve problems with their peers. As part of the Grace and Courtesy curriculum, children prepare and share snacks within the classroom. They are given lessons on appropriate meal behavior and sometimes teachers will join students at the lunch table to model appropriate meal behavior.

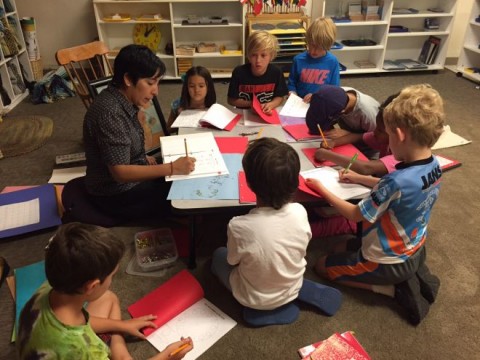

- Small Group Lessons: Though many lessons are presented to students individually, at all levels students participate in small group lessons. These lessons allow students to express their thoughts and ideas in a safe environment. As they dialogue with one another regarding their thoughts about a particular subject, teachers can assess conversational skills as well as how much or little a child may be grasping an important concept. When a child is uncertain or misunderstands a concept, teachers will represent material in a different way or within a different setting rather than reprimanding or shaming a child for misunderstanding. In these group lessons, students learn to listen to and respect other children’s perspective.

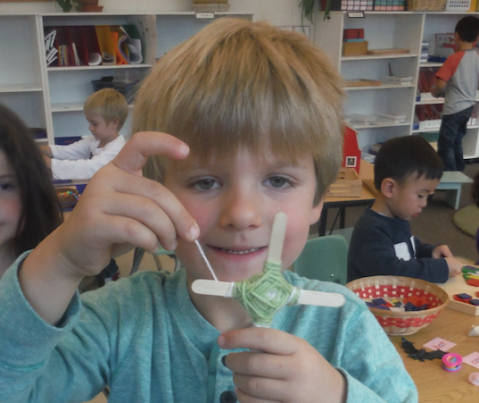

- Care of Environment: At entry into a Montessori environment children are given lessons on care of the environment around them. They are taught that the space in which they learn is their space, it belongs to them. They are taught the value of community and learn their role in a community. They are also taught to respect and value the roles of their peers within the same community.

- Freedom to solve problems: Along with lessons on how to solve problems, children are given the freedom to actually practice the skill in a safe environment with caring and observant adults nearby. Montessori believed that children like to work out their own social problems and she said, “When adults interfere in this first stage of preparation for social life, they nearly always make mistakes….Problems abound at every step and it gives the children great pleasure to face them. They feel irritated if we intervene, and find a way if left to themselves.” In order to accommodate this freedom, teachers use lunch, recess, and transition times to continually model appropriate social interactions. The time for lessons does not stop once the bell to step outside the classroom rings.

- Lack of Competition: Mixed age classrooms, individual progression, and self-correcting materials are all contributors to the ability to avoid competition among children in a Montessori environment. Students have a natural tendency to assist one another and collaborate. Oftentimes only one material of its kind will exist within a classroom, teaching children patience as well as allowing them to plan ahead, and accommodate change. Montessori said, regarding classroom materials, “The chid comes to see that he must respect the work of others, not because someone said he must, but because this is a reality he meets in his daily experience.”

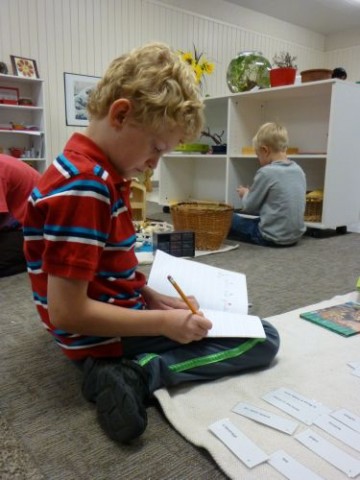

- Self-Correcting Materials: Work in the environment is set up to allow the child to use the materials to check their work. As students discover mistakes for themselves, the ability to correct becomes innate and they do not lack confidence for fear of being told they are wrong. It also allows the children to have purposeful movement.

- Celebration of Individuality: As students are allowed the opportunity to choose what to work on and how long to spend on an activity and the ability to not be rushed to understand concepts, they are able to celebrate their individuality. Some children will grasp a concept more easily than another, some students will embrace one subject at a different time than their peers and as they work with those sensitive periods they grow as individuals. Then, within their roles as an important part of the classroom community, they are able to share concepts with others.

In these ways and others, children in a Montessori environment are given the very best opportunities for appropriate social development.

May we all increase our efforts to make peace. May we all have peaceful hearts. May we all believe in the beauty of a future full of hope, love and peace.With love,

May we all increase our efforts to make peace. May we all have peaceful hearts. May we all believe in the beauty of a future full of hope, love and peace.With love,